Return

to Page 1

Return to Page 2

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton

(1874 - 1922)

Shackleton, the man

and early expeditions

The Crew

(see Obituaries below for much more info. on the crew)

The Expedition seen through

the pictures of Frank Hurley

Ernest Henry Shackleton was born on the 15th February in 1874 in Kilkea House, County Kildare in Ireland. The second in a family of ten, his father Henry was a farmer at Kilkea. His mother Henrietta was descended from the Fitzmaurices, a family which had been in Kerry since the Norman times in the 13th century.

In 1880 when Ernest was six his father gave up farming and went to Trinity College Dublin, and qualified to be a doctor. The family lived at 35 Marlborough Road in Dublin and in 1884 they moved to Sydenham in South London where Henry practiced for 30 years.

Romantic, ambitious, handsome and strong, Shackleton preferred the idea of going to sea than into medical practice and joined the merchant navy when he was 16. His first voyage included a memorable rounding of Cape Horn in winter: 'one continuous blizzard all the way', he recalled later. His captain reckoned he'd never come across such an 'obstinate boy'.

He qualified as a master mariner eight years later in 1898. His years at sea took him to Japan, America and South Africa, but he dreamed of exploring the poles. In 1900, he co-authored O.H.M.S, a book about his experience of transporting British troops to fight in the Boer War.

Keen for glory, Shackleton's first polar experience was aboard Discovery as third lieutenant in charge of provisions on Captain Scott's Antarctic expedition of 1901-4. He was one of the three members who journeyed over the Ross ice shelf by sledge, but was invalided home with scurvy in 1903. The following year, he married Emily Dorman, one of his sisters' friends, and they subsequently had three children. [The Discovery is on display in Dundee, Scotland and is well worth a visit. You can see Shackleton's name on his cabin door]

After leaving maritime service in 1904, he did a stint as a journalist before being elected to the full-time post of secretary of the Scottish Royal Geographical Society. In 1906, he stood unsuccessfully for Parliament as a Liberal-Unionist in Dundee, then

joined an engineering firm in Glasgow. But he was already preparing for his next journey south.

In 1908, he returned to the Antarctic as leader of his own expedition, with the whaling ship Nimrod. His sledging party made it to within 97 miles of the South Pole, the furthest south anyone had been, despite being ill-equipped with ponies instead of trained dogs. Faced with blizzards and dwindling rations, Shackleton turned back short of his goal to save his men's lives. However, the expedition did result in the claiming of the Victoria Land plateau for Britain, and Shackleton received a knighthood on his return. His dictated account, The Heart of the Antarctic, was published in 1909.

Sir Ernest's third - and most famous - trip was in 1914 as leader of the British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The plan was to cross Antarctica from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea via the pole, a distance of some 1,800 miles.

On August 8th the Endurance sailed for the Antarctic via Buenos Aires and the sub Antarctic island of South Georgia where there was a Norwegian whaling station. It was thought that the war would be over within six months so when it came time to leave for the south, they left with no regrets.

Sir Ernest Shackleton Expedition Leader Frank Worsley Captain Frank Wild Second-in-command Lionel Greenstreet First Officer Tom Crean Second Officer Alfred Cheetham Third Officer Frank Hurley, Photographer George Marston Artist Robert Clark Biologist Leonard Hussey Meteorologist Reginald James Physicist James Wordie Geologist Alexander Macklin Surgeon James McIlroy Surgeon Hubert Hudson Navigator Charles Green Cook Henry McNeish Carpenter Louis Rickinson Engineer Ernest Holness Stoker William Stephenson Stoker William Bakewell Seaman Walter How Seaman Thomas Orde-Lees Ski Expert and Storekeeper Perce Blackborow Steward John Vincent Boatswain Alfred Kerr Engineer Timothy McCarthy Seaman Thomas McLeod Seaman

Shackleton

Frank Worsley

Tom Crean

Henry McNeish

On November 5th they arrived at South Georgia. Shackleton learnt much from the whaling captains about the conditions between

there and the Weddell Sea. The plan had been to spend only a few days collecting stores, but instead the Endurance remained at South Georgia for a month to allow the ice further south to disperse. This month was one where bonds of friendship and mutual respect were formed between the Endurance crew and the Norwegian whalers. Bonds that were to prove unexpectedly useful some time later to Shackleton and his men.

The Weddell Sea was known to be particularly ice bound at the best of times and the Endurance left with a deck-load of coal in addition to normal stores to help with the extra load on the engines when it came to pushing through pack ice in the Weddell Sea to the Antarctic continent beyond. Extra clothing and stores were taken from South Georgia in the event that the Endurance may have to winter in the ice if caught in the Weddell Sea as it froze, unable to reach the continent first. They left South Georgia on the 5th of December 1914

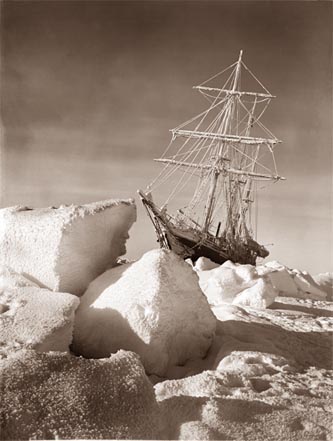

The Endurance battled her way through a thousand miles of pack ice over a six week period and was one hundred miles - one days sail - from her destination, when on the 18th of January 1915 at 76°34'S, the ice closed in around her. The temperature dropped dramatically cementing together the loose ice that surrounded the ship.

For Shackleton, the disappointment must have been bitter, he was 40 years old, his country was at war, the expedition had taken huge amounts of effort and energy to prepare, he was unlikely to have this opportunity again.

Nevertheless, his men looked towards "the Boss" as they called him. This collection of Royal Naval sailors, rough and ready trawler hands and recent Cambridge University graduates amongst others were now dependent on the man who had led them to this place and this very unfortunate predicament.

The ship was drifting to the southwest with the ice. Attempts were made to free the ship when sometimes cracks appeared in the ice nearby, but to no avail. The ice around the ship itself was thick and solid. Men with heavy improvised ice chisels and iron bars breaking the ice up near the ship and the ship at full speed ahead had no effect at all and the ship continued to drift.

By the end of February, temperatures had fallen and were regularly -20°C, the ship was now clearly frozen in for the winter. The worry was where the drifting ice would take them and would it be possible to break out in the spring? The sides of the ship were cleared so that if the ice began to press together, then hopefully the Endurance would be able to rise above the ice and ride on it rather than being crushed.

This eventuality had not really been planned for and the men became frustrated and restless, football and hockey games were regular features on the sea ice until the darkness of the Antarctic winter began. Sunrise glows came in early July heralding the return of the sun and daylight, but the weather was not kind with regular blizzards and low temperatures. Most worrying of all was the pressure from the ice, floes began to "raft" over each other.

Everyone knew that one of two things would happen, either the pack ice would thaw, break up and

disperse in the spring, so freeing the ship, or it would consolidate and driven by the effects of wind and tide over hundreds of miles of sea would take hold of and crush the ship - like a toy in a vice.

Shackleton wrote

"The ice is rafting up to a height of 10 or 15 ft. in places, the opposing floes are moving against one another at the rate of about 200 yds. per hour. The noise resembles the roar of heavy, distant surf. Standing on the stirring ice one can imagine it is disturbed by the breathing and tossing of a mighty giant below"

The men went out to look for fresh meat for the dogs and themselves in the form of seals and penguins, they were still in low supply having disappeared at the start of winter, a few were taken at the end of September.

On Sunday, October 23rd their position was 69°11'S, longitude 51°5'W. The Endurance was under heavy pressure from the ice and not held in a good position, instead of being able to slip upwards with the increasing pressure, the ice had hold of her. The first real damage was to the stern-post which twisted with the planking buckling in the same area, she sprang a leak. The bilge pumps were started and the leak was initially kept in check.

On October 27th Shackleton wrote, "The position was lat. 69°5'S, long. 51°30'W. The temperature was -8.5°F, a gentle southerly breeze was blowing and the sun shone in a clear sky. After long months of ceaseless anxiety and strain, after times when hope beat high and times when the outlook was black indeed, we have been compelled to abandon the ship, which is crushed beyond all hope of ever being righted, we are alive and well, and we have stores and equipment for the task that lies before us. The task is to reach land with all the members of the Expedition. It is hard to write what I feel".

The Endurance had drifted at least 1186 miles since first becoming fast in the ice 281 days previously, she was 346 miles from Paulet Island, the nearest point where there was any possibility of finding food and shelter.

Shackleton ordered the boats, gear, provisions and sledges lowered onto the ice. The men pitched five tents 100 yards from the ship but were forced to move when a pressure ridge started to split the ice beneath them. "Ocean Camp" was established on a thick, heavy floe about a mile and a half from what was fast becoming the wreck of the Endurance.

The Endurance finally broke up and sank below the ice and waters of the Weddell sea on November 21st 1915. The men had saved as many supplies as they could (including Frank Hurley's precious photo archive) before she disappeared.

The 28 men of the expedition were now isolated on the drifting pack ice hundreds of miles from land, with no ship, no means of communication with the outside world and with limited supplies. What was worse was that the ice itself was now starting to break up as the Antarctic spring got under way. On December 20th Shackleton decide that the time had come to abandon their camp and march westward to where they thought the nearest land was, at Paulet Island.

They had three lifeboats named after patrons of the expedition who had donated funds. Two of these were now man hauled in relays, the James Caird and Dudley Docker. The third boat, the Stancomb Wills was left behind. If the ice began to disappear under them, the men would take to the 20 foot boats.

Shackleton wrote, On New Year's Eve 1915

"Thus, after a year's incessant battle with the ice, we had returned to almost the same latitude we had left with such high hopes and aspirations twelve months previously; but under what different conditions now! Our ship crushed and lost and we ourselves drifting on a piece of ice at the mercy of the winds"Some of the men led by Frank Wild returned to the area where the Endurance had been to retrieve the Stancomb Wills. They were all forced into the boats on April 9th and made their way across a stretch of open water, by the evening they were able once again to haul the boats onto a large ice floe and pitch their tents.

That the men kept going during this time was a tribute to Shackleton's leadership skills and his abilities and understanding of the importance of keeping up morale. The whole group were kept together in the monotonous and strenuous task of pulling laden lifeboats across broken up and ridged ice floes. It was now 14 months since the Endurance had become frozen into the ice and nearly 5 months since she had sank marooning them in a featureless icy wilderness. On April 12th Shackleton found that instead of making good progress westwards, they had actually travelled 30 miles to the east as a result of the drifting ice. They did however spot Elephant Island, part of the South Shetlands group and headed that way in seas that were by now largely open for navigation. They made landfall on Elephant Island being ecstatic to do so. It had been 497 days since they had last set foot on land.

Their first landing place wasn't an ideal site for a camp and so they took to the boats again and soon found a more appropriate place to make camp.

Shackleton wrote

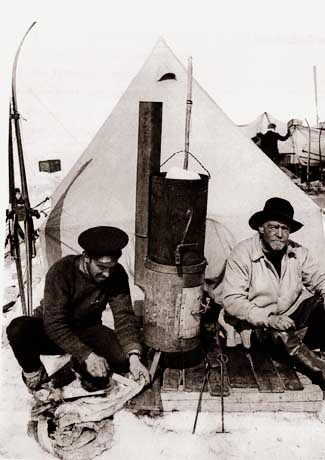

"As we clustered round the blubber stove, with the acrid smoke blowing in our faces, we were quite a cheerful company...Life was not so bad. We ate our evening meal while the snow drifted down from the surface of the glacier and our chilled bodies grew warm"

For the time being they were more safe and secure than they had been for a long time, but they were still stranded far from civilization with no-one knowing where they were or what their condition was. There was no chance of rescue. No ships passed that way. No radio at that time was capable of summoning help.

The outside world was not going to come to Elephant Island.

Shackleton realised that in order to effect a rescue, he was going to have to travel to the nearest inhabited place which was the whaling station back on South Georgia, some 800 miles distant and across the most stormy stretch of ocean in the world. They expected to encounter waves that were 50 feet from tip to trough "Cape Horn Rollers" in a 22 foot long boat. Their navigation was by a sextant and a chronometer of unknown accuracy, they were dependent on sightings of the sun that could sometimes not be seen for weeks in the overcast weather so characteristic of these latitudes.

Shackleton chose Frank Wild to stay behind with the men on Elephant Island as he felt that he could hold them together well. If there was no rescue by the spring they were to try and reach Deception Island.

The party left behind on Elephant Island used the two remaining life boats to make a hut, they were turned upside down and placed on top of two low stone walls, tent and sail fabric were used as lining to keep the wind and weather out. The men were even able to make small celluloid windows from an old photograph case, a blubber stove provided heat and was used as a cooker. Conditions were cramped and food was in short supply. One of the party, Blackborrow, (little more than a boy who had joined the ship as a stow-away in Buenos Aries when his companion had been hired though he had not) suffered from frostbitten toes. These were amputated by the surgeons by the meager light given out by the blubber stove.

The lifeboat chosen for the journey was the James Caird, it was made seaworthy by whatever limited means were available and equipped with a part cover against the weather and the sea. Launching her was eventful with many of the men being soaked to the skin, a serious matter in the cold climate and with very limited facilities for drying their clothes out and getting warm again.

The James Caird set off on the 24th of April, the very last day before the pack closed in again on a day of relative calm. The crew was Shackleton, Worsley, Crean, McNeish, McCarthy and Vincent, the anticipated journey time was a month. It was to become one of the most astonishing small boat journeys of all time.

The James Caird made progress at the rate of around 60-70 miles per day though the sea conditions were rough. The sea constantly came in and made everything including the sleeping bags wet, it was difficult to find any warmth at all. There were four sleeping bags made of reindeer hide which shed their hairs in the constant dampness, making them less effective and clogging the pump used to empty the sea water that spilled over into the boat.

The boat was relatively unladen and so boulders and other ballast had been placed aboard in order to trim her, these had to be constantly moved around. The weather worsened and they encountered fierce storms, As the temperature dropped, ice formed on the outside of the boat from frozen sea spray, up to 15 inches deep on the deck. This made the boat much heavier and affected the trim - more moving around of the boulders - the men also tried as far as they could to chip away the accumulated ice with any tools that they could improvise, though the situation worsened. They began to throw items overboard in order to save weight, the spare oars went as did two sleeping bags that by now were soaked through and hard and heavy with ice.

At other times they had to bale out water for dear life, the only solace during this journey were hot meals every four hours by the light of a primus stove.

They had been drifting for some time under light sail held back by the sea anchor due to the sea state (a sea anchor is a sort of large canvas bag that acted to slow the boat and prevent it from being tossed around quite so violently during stormy seas). The sea anchor however was lost as the boat fell into a large trough between waves and the men then had to beat the canvas sails free of ice and set them again properly in order to keep on course.

Frostbite was beginning to affect exposed fingers and hands in the cold and constant wet. Navigation was also a problem due to the continually overcast weather. On the seventh day at sea however a break in the cloud came and Worsley was able to take a reading from the sun, six days since the last observation, he calculated that they had travelled around 380 miles and were almost half-way to South Georgia. The short period of sunshine meant that the men were able to spread their clothing and other gear over the boat deck and the mast to dry out. The ice became less dense and they occasionally were accompanied by wildlife, porpoises and tiny storm petrels.

Shackleton was at the tiller on may 5th, the eleventh day out at sea. The sea had become much rougher,

"I called to the other men that the sky was clearing, and then a moment later I realized that what I had seen was not a rift in the clouds but the white crest of an enormous wave."

"During twenty-six years' experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic. "

"It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days. I shouted 'For God's sake, hold on! It's got us.' Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We baled with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us"

On May 7th Worsley again was able to take a navigational reading and reckoned that they were not more than a hundred miles from the northwest corner of South Georgia, another two days with the wind with them and they should have the island within sight. On the morning of the 8th of May, they began seeing kelp floating in the sea, then some sea birds, just after noon they caught a glimpse of South Georgia, only fourteen days after leaving Elephant Island and about half as long as they thought the journey would take.

Landing was to be a less than straightforward affair, reefs (shallow rocks just below the sea surface) stretched all along the region of the coast where they were and great waves broke over them. The rocky coast in many places descended steeply into the sea. Despite being so close and running out of fresh water to drink, they had no choice but to wait for the next morning to break before attempting to land on the shore.

The morning brought a shift in the wind and a terrible storm arose, the James Caird was tossed around in the sea and when light broke, they were out of sight of land once again. They made their way back to South Georgia just after noon, but again, it was a coast of huge breakers and sheer cliffs that greeted them. The day wore on and there seemed no hope, later though in the evening, the wind shifted direction and began to die down. By the morning of the 10th of May, there was very little wind and they were able to look for a landing place. Reefs and breaking waves dogged their every attempt. They found a likely bay to land, but were blown out to sea again by a change in the wind. In approaching darkness they eventually were able to enter a small cove fronted by a reef, they had to take in the oars to pass through, but at long last, carried by the swell, the James Caird was able to land on a South Georgia beach at King Haakon Bay.

They had got through thanks to Shackleton's leadership and the incredible navigational skills of New Zealander Frank Worsley. Worsley had only been able to take sightings of the sun four times, on April 26th and May 3rd, 4th and 7th, all the rest had been dead reckoning.

Had they failed to land, the boat would have been swept onwards to be lost in the mid Atlantic, and no rescue party would have set out for the men on Elephant Island.

They had landed 22 miles from the Stromness whaling station as the crow flies. In order to get there they had to go across the backbone of mountains that ran the length of South Georgia, a journey that no-one had ever managed, the map depicted the area as a blank.

McNeish and Vincent were too weak to attempt the journey so Shackleton left them with MaCarthy to care for them. On May 15th Shackleton, Crean and Worsley set out to cross the mountains and reach the whaling station, they crossed glaciers, icy slopes and snow fields. At a height of about 4500 feet, they looked back and saw the fog closing up behind them. Night was falling and with no tent or sleeping bags, they had to descend to a lower altitude. They coiled a rope and slid down a snowy slope in a matter of minutes losing around 900 feet in the process. They had a hot meal with two of them sheltering the cooker from the wind. Darkness fell and they carried on walking, with a full moon lighting their way. They climbed again and ate another hot meal to renew their energy.

They were soon able to make out an island in the distance that they recognized, but realised that they had taken the wrong direction and had to retrace their steps. At 5 a.m. they sat down exhausted in the lee of a large rock wrapping their arms around each other to keep warm. Worsley and Crean fell asleep, but Shackleton realised that if they all did so, they may never wake again. He woke them five minutes later and told them they had been asleep for half an hour, once again they set off.

There was now but one ridge of jagged peaks between them and Stromness, they found a gap and went through. At 6.30 a.m. Shackleton was standing on a ridge he had climbed to get a better look at the land below, he thought he heard the sound of a steam whistle calling the men of the whaling station from their beds. He went back to Worsley and Crean and told them to watch for 7 o'clock as this would be when the whalers were called to work. Sure enough, the whistle sounded right on time, the three men must have never heard a more welcome sound.

"Boys, this snow-slope seems to end in a precipice, but perhaps there is no precipice. If we don't go down we shall have to make a detour of at least five miles before we reach level going. What shall it be?"

"Try the slope".

The three walked downwards to 2000 feet above sea level. They came across a gradient of steep ice, two hours later, they had cut steps and roped down another 500 feet, a slide down a slippery slope placed them at 1500 feet above sea level on a plateau. They still had some distance to go before they reached the whaling station. The going was still less than easy and they had some climbing still to do to negotiate ridges between them and their goal.

At 1:30 p.m. they climbed the final ridge and saw a small whaling boat entering the bay 2500 feet below. They hurried forward and spotted a sailing ship lying at a wharf. Tiny figures could be seen wandering about and then the whaling factory was sighted. The men paused, shook hands and congratulated each other on accomplishing their heroic journey.

"..... we had entered a year and a half before with well-found ship, full equipment, and high hopes. We had 'suffered, starved and triumphed, grovelled down yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the whole.' We had seen God in His splendours, heard the text that Nature renders. We had reached the naked soul of man"

The whaling station, was now just a mile and a half away. They tried to smarten themselves up a little bit before entering the station, but their beards were long, their hair was matted, their clothes, tattered and stained as they hadn't been washed in nearly a year. At 3 o'clock in the afternoon of May 20th, they walked into the outskirts of Stromness whaling station, as they approached the station, two small boys met them. Shackleton asked them where the manager's house was and they didn't answer, they just turned and ran from them as fast as they could. They came to the wharf where the man in charge was asked if Mr. Sørlle (the manager) was in the house.

Mr. Sørlle came out to the door and said, "Well?"

"Don't you know me?" I said.

"I know your voice," he replied doubtfully. "You're the mate of the Daisy." (the Daisy was the last of the American open boat whalers, it had visited South Georgia in 1913)

"My name is Shackleton," I said.

Immediately he put out his hand and said, "Come in. Come in."They washed, shaved, ate and slept. Worsley boarded a whaler went to rescue the three left on the other side of South Georgia at King Haakon Bay sheltering under the upturned James Caird. During this rescue a storm blew up that had it come the day previously could have spelled disaster for the three men crossing to Stromness and consequently the whole of the crew, those on the wrong side of South Georgia and all those on Elephant Island.

Shackleton remained at Stromness and prepared plans for the rescue of the men on Elephant Island. Shackleton, Worsley and Crean left on the British whale catcher Southern Sky that had been laid up for the winter bound for Elephant Island on the 23rd of May.

Later, Shackleton was to write in a letter to a friend,

"When we got to the whaling station, it was the thought of all those comrades that made us so mad with joy...We didn't so much feel safe as that they would be saved"Sixty miles from the island the pack ice forced them to retreat to the Falkland Islands whereupon the Uruguayan Government loaned Shackleton the trawler Instituto de Pesca but once again the ice turned them away. They went to Punta Arenas where British and Chilean residents donated £1500 to Shackleton in order to charter the schooner Emma. One hundred miles north of Elephant Island the auxiliary engine broke down and thus a fourth attempt would be necessary. The Chilean Government now loaned the steamer Yelcho, under the command of Captain Luis Pardo, to Shackleton.

As the steamer approached Elephant Island, the men on the island were approaching lunchtime. It was August 30th 1917 when Marston spotted the Yelcho in an opening in the mist. He yelled, "Ship O!" but the men thought he was announcing lunch. A few moments later the men inside the "hut" heard him running forward, shouting, "Wild, there's a ship! Hadn't we better light a flare?" As they scrambled for the door, those bringing up the rear tore down the canvas walls. Wild put a hole in their last tin of fuel, soaked clothes in it, walked to the end of the spit and set them afire.

The boat soon approached close enough for Shackleton, who was standing on the bow, to shout to Wild, "Are you all well?". Wild replied, "All safe, all well!" and the Boss replied, "Thank God!" Blackborrow, since he couldn't walk, was carried to a high rock and propped up in his sleeping bag so he could view the scene. Within an hour they were headed north to the world from which no news had been heard since October, 1914; they had survived on Elephant Island for 105 days.

In 1921 Shackleton was once more drawn back to Antarctica in an attempt to map 2000 miles (3200 km) of coastline and conduct meteorological and geological research. Although he was only 47, he died of a suspected heart attack on board the Quest as she was at anchor in King Edward Cove, South Georgia. Shackleton was buried on South Georgia and his death brought to a close the "Heroic Age" of Antarctic exploration. The grave was marked by a headstone of Scottish granite in 1928 and is visited regularly by scientists and tourists to this day.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Shackleton's Boat Journey by FA Worsley

Endurance - An Epic of Polar Exploration by FA Worsley